Challenges and Survival

The Trust’s Declaration, 1540

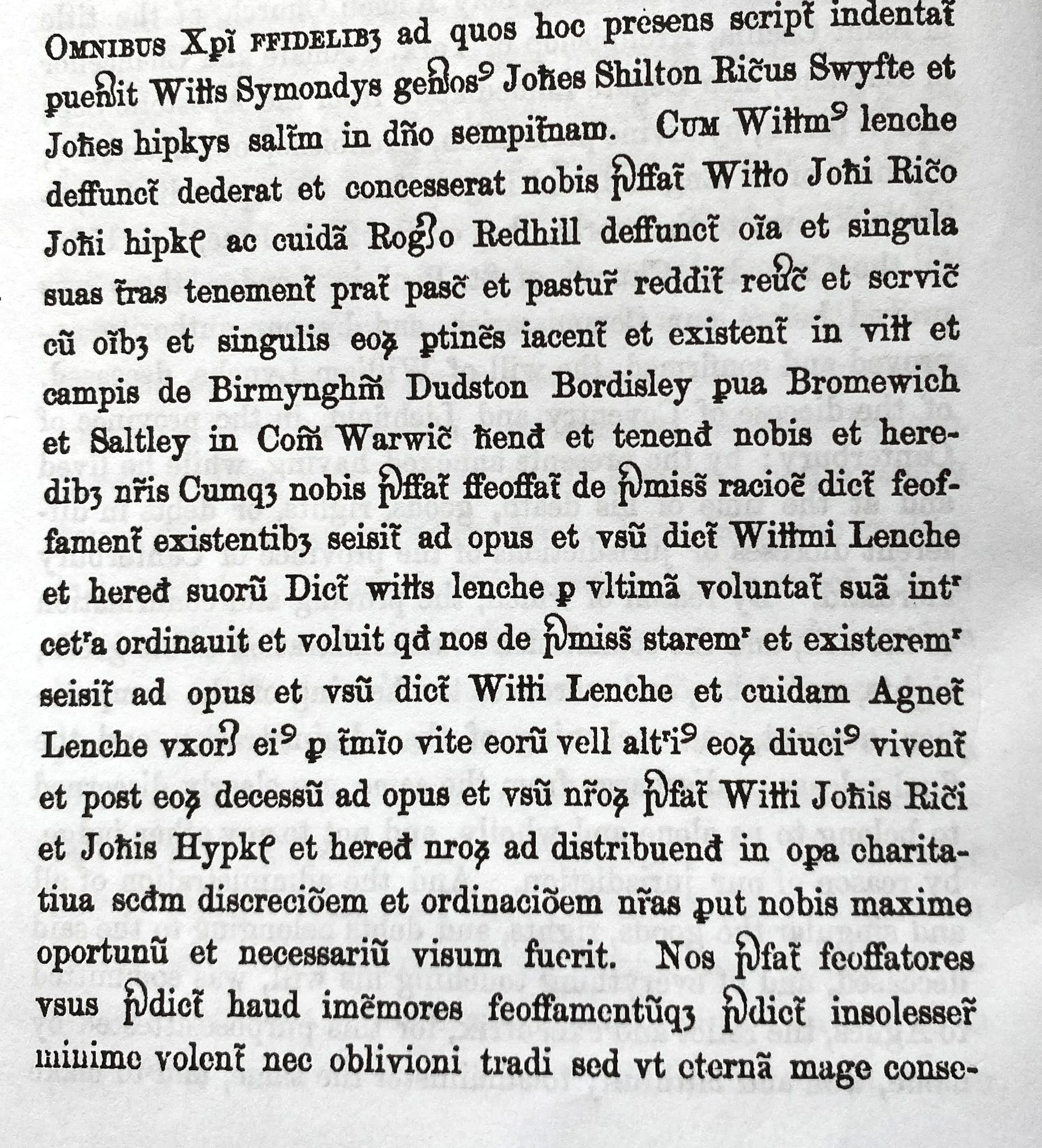

William Lench died in 1526, and probate of his will was granted on 26th June in the joint names of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey Archbishop of York and Chancellor of England, and William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury. Then the most powerful man in England after the king, Wolsey was soon to lose favour for his failure to have Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled by the Pope. It seems that 13 years later, Agnes Lenche died and the Deed of Enfeoffment should have come into effect. Instead, an effort was made to thwart it.

John Marsh was grandson of John Lenche, William’s uncle, and saw himself as the heir to the property and as such its owner. Swiftly, he sought to make money from it. In April 1539, he sold 20 acres of pasture in Duddeston, other properties and all of what he termed, “my lands, tenements, and rents in Birmingham”.

The plaque commemorating William Lenche in St. Martin’s Church in the Bull Ring.

In response, the four living Trustees who were the close friends of Lenche made the first Declaration of the Trust on 29 March 1540. Probably led by William Symonds, the others were John Shilton, Richard Swyft, and John Hipkys – Roger Redhyll having died. They made it clear that after the deaths of William and Agnes and by right of the Deed of Enfeoffment, they and their heirs “should stand and be seized of the premises … to distribute in works of charity according to our discretion and ordering, where we shall see the greater want”. Emphasising that they desired “by no means the said feoffment should be disused nor forgotten but rather that it may be held in everlasting remembrance”, they made grants of rental property to various people. These brought into sight Lenche’s remaining holdings in the Trust: two tenements and land in Moor Street; a barn and a croft near to the Pinfold, where stray animals were kept in a pen and hence Pinfold Street; the Callowfields in Bordesley; and Hawke’s Croft, pasture in part of what became the Gun Quarter and later the Trust’s St. Mary’s Estate.

The Declaration then listed other Trustees, including William Colmore the elder, the only other survivor of the original 19. Two others did have close connections with them. They were Roger Hawkes, a servant of Lench, who was probably the son of William Hawkes, and John King, a relative of William King.

Smallbrook Queensway in early 1962, recalling the Smalbrokes, several of whom served as Trustees of Lench’s. On the left is Ringway House designed by James Roberts, who also designed the Rotunda, and, on the right, the Albany Hotel is nearing completion.

A fuller producing cloth from sheep’s wool, John King had a fulling mill in Edgbaston and a dying house. The inventory of goods and chattels in his will of 1556 amounted to a considerable sum of £90.

One of that will’s witnesses was Richard Smalbroke, another new Trustee who’d soon gain the prestigious and powerful office of High Bailiff, ensuring the legality of weights and measures in the town’s markets. Recalled in Smallbrook Queensway, one of his sons was responsible for building Blakesley Hall, amongst Birmingham’s oldest and most historically significant buildings and now a museum. As for Richard himself, he owned shops which he leased out and held property in Birmingham, Yardley, West Bromwich, and Bordesley, including the Ravenhurst Estate at Camp Hill that’s remembered in Ravenhurst Street. After his direct line died out, his lands went through marriage to the Vyse family, hence Vyse Street in the Jewellery Quarter.

Smalbroke was also active in the wills of two other new Trustees, both of whom were wealthy tanners. The first was Henry Foxall, the son of Roger Foxall, a supervisor of Lenche’s will; and the second was Thomas Marshall, whose goods were valued at a little over £130 after his death. He also bequeathed almost £60 in gold, silver, and money, whilst his will indicated that he’d lived in style in Park Street.

Two other newcomers to the Trust joined Smalbroke as amongst the most influential men in Birmingham: Humphrey Colchester was Master of the Guild of Holy Cross, and Robert Vernon was Birmingham’s Low Bailiff, an officer of the Leet. In effect, this was the common assembly and court of justice of the township with Vernon summoning its juries and charging stallholders at the local fairs. The final new Trustees were Thomas Cowper, a prosperous scythesmith; landholders William Bogie and John Willeys; and John Vesey. Like Lench, Vesey was a grazier.

Indeed, he was one of the foremost locally, having numerous sheep folds, meadows, fields, and barns. Classed as a yeoman because he also held a small landed estate, he was below the rank of a gentleman but well above the generality of the population.

After their naming, the Trustees stated their intent to apply and distribute all income and profits arising from the lands and tenements in the Trust, setting out how they’d do that. Chosen annually with the assent of the majority, two of the feoffees would receive the money and use it to repair the ruined ways and bridges in and about Birmingham where there was need. In default of this, the rents and profits would be bestowed upon the poor living in the town where there was the greatest want, or else given over to other godly uses. At the end of each year, the assigned pair of feoffees would give a reasonable account of their distribution and nondistribution to their fellows in the chapel of St. Katherine in St. Martin’s. Any funds not spent would be delivered to the other Trustees. After seven of the Trustees died, the survivors would enfeoff certain of the worthiest men of Birmingham.

The first page of the First Declaration of the Trust in 1540, written in Latin.

Empowered by the wealth and influence of 16 of the town’s most significant citizens, the Trustees acted vigorously to regain control of their properties taken and sold by Lenche’s second cousin, Marsh. In October 1540, Jasper Smythe, alias Hoysen, released all his claims to various lands, tenements, rents, and services in Birmingham and elsewhere to the Trustees. Much more of Lenche’s Estate was bought from Marsh by Edward Pye, a gentleman of Ward End, then on the outskirts of Birmingham. On 2 April 1541, an Indenture of Arbitration settled all variance, strife, and debate arising from divers ambiguities and doubts concerning Marsh’s heirship and the feoffment, with Pye receiving £20 in full satisfaction of all claims. Six months later, he received a further £10 for his final release of all claims and deeds of Lenche’s lands.

More difficulty was had in pursuing claims against Thomas Holte, who’d bought substantial lands, tenements, rents, reversions, and services from Marsh’s daughter, Margaret. A big landowner owning the manors of Nechells, Duddeston, and Aston, Holte was a successful and unscrupulous lawyer benefitting from Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries.

Failing in his attempts to get the Pope to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon, Henry VIII broke with papal authority and in 1534, the Act of Supremacy made him Supreme Head of the Church in England. This was quickly followed by two acts of suppression disbanding Roman Catholic monasteries, priories, convents, and friaries, and allowing the king to seize their wealth and dispose of their assets. Looking for a swift return on his new estates, he sold them at competitive prices, giving his henchmen an unparalleled opportunity to increase their holdings, status, and influence.

Amongst those taking advantage was Holte, probably one of the Visiting Commissioners appointed by the king to oversee the dissolution regionally. On the same day as Pye’s final release in favour of the Trustees, 6 April 1541, Holte did the same. The strength of the Trustees was underscored by their determination to challenge such a formidable opponent, yet it was only a partial victory because Lenche’s lands in Aston and Duddeston were not included. They were lost, in all likelihood, to Holte.

Loveday Croft and Expansion

Under Henry’s son, Edward VI, a final attack was made on Catholic religious bodies. In 1547, all religious guilds were dissolved with their property confiscated by the crown and sold on. In Deritend, the Guild of St. John disappeared. So too did Birmingham’s Guild of the Holy Cross, although Richard Smalbroke and others petitioned successfully for some of the funds raised from the sale of its estates and other property to be restored for educational purposes. This led to the 1552 charter founding the King Edward VI School, which was supported by grants of land, including the site of the Guild House. The 20 Governors of the new school almost replicated Lench’s existing Trustees. In addition to Smalbroke others were Symonds, Shilton, Swyft, Colmore the elder, Marshall, Foxall, Vesey, Bogie, King, Cowper, and Willeys. Three more governors were closely connected to the Trust: Paynton; William Colmore the younger; and Ascrick, an original Trustee.

Lench’s Trust was fortunate not to be dissolved as its provisions were practically the same as those granted to the Guild of the Holy Cross in 1392. In his pioneering work on English Guilds, Joshua Toulmin Smith believed that even though the Trust didn’t maintain a priest, it escaped for two reasons. Firstly, it was called a trust and not a guild and secondly, it was established by enfeoffment and not by a licence in mortmain, a document issued by the Crown for the alienation or conveyance of lands to a monastery or other corporation. Having survived, Lench’s gained from a donation of William Colmore the elder. In his will of 1566, he gave it an annuity or yearly rent charge of 10 shillings from a house with outbuildings and some land in Corn Cheaping, close to the top of Moor Street and now part of the Bull Ring. Another more substantial addition was more puzzling in how it came about. This was the four acres of Loveday’s Croft, later part of the St. Mary’s Estate and remembered in Loveday Street. In his Canterbury Tales, Chaucer stated that the friar “in lovedays there could he much help”, indicating that on such occasions he would facilitate the amicable settling of disputes in certain spots. According to tradition, Loveday Croft was so named because it was given over by John Cowper for the making of lovedays amongst Birmingham men.

This belief was strengthened by entries in the Trust’s minute books. Kept from 1771, they recorded payments from Loveday Croft’s rents of 2 shillings 6 pence a time or for “composing a difference”, “temporising a difference”, “an arbitration”, “making up a lawsuit”, and “making peace”. Joseph Hill, a dedicated researcher into Birmingham’s past, believed that the payments actually didn’t begin until many years after Lench’s was founded. In support, he noted that the earliest relevant deed for Loveday Croft from 1564 indicated it was leased to William Cowper, scythesmith, for a payment of £5 “towards the repairing and amending of the Stone Bridge, called Rea Bridge, in Birmingham … in ruin and decay”. Formerly looked after by the Guild of the Holy Cross, its condition had deteriorated badly since its dissolution.

The 1524-25 Lay Subsidy recorded a John Cowper (Cooper) as amongst the wealthiest men in Birmingham and it may be it was he who put Loveday Croft in trust. Although no documentary evidence exists, the 1564 document did name three Trustees. They were Thomas Cowper, Richard Smalbroke, and John Vesey, all of whom were also feoffees of Lench’s. By 1584, only Vesey survived in both trusts and that year, he joined with William Bothe, a yeoman, in bringing Loveday Croft into Lench’s – although only Vesey is commemorated in a street name. This was achieved by conveyance of the properties to a pair of intermediate Trustees, William Severne, tanner, and William Woodwall, Master of the Free School (King Edward VI). Two years later, they conveyed Lenche’s lands to Vesey, Bothe, and 12 other Trustees. Amongst them were the sons or close relatives of previous feoffees: John Shilton, mercer; William King, ironmonger; William Colmore the younger and his cousin, Ambrose the younger, both mercers; and Thomas Smalbroke, yeoman.

The new names included John Ward the elder, a wealthy yeoman owning land and buildings in Birmingham, Aston, Little Bromwich, Castle Bromwich, and Bordesley; and his cousin, John Ward, a prosperous baker whose father set up a trust that would become part of Lench’s. Edward Smith was connected to them through his wife, Joan. She was a daughter of William Colmore the elder and after his death, her widowed mother (also Joan) married John Ward the elder. The Trustees’ numbers were made up with other well-to-do men: Robert Rastell, draper; Thomas Smith, wine merchant; Thomas Selman, whose goods and chattels were worth £55 when he died in 1603; and Robert Whittall, ironmonger, one of whose descendants bought the Crossfields Estate close to Loveday Croft and is brought to mind by Whittall Street by the Children’s Hospital.

Built upon from the late 1700s, Loveday Croft was transformed into Loveday Street amid Birmingham’s Gun Quarter as shown by the St. Mary’s Works of the renowned gunmaker, W. W. Greener.

No documents relating specifically to the Trust survived between 1586 and 1613 when the two remaining Trustees, Whittall and Ambrose Colmore, made 12 new feoffees and renewed the settlement of Lenche’s lands. Amongst them were familiar names: three more of the Colmore family, two Smalbrokes, and another Smith and Whittall. They were joined by Roger Pemberton, a rich goldsmith whose descendants became Quakers and who, through marriage, brought the banking Lloyds to Birmingham from Wales. The final four Trustees were Edward Lea, a woollen draper from a well-established family, and three tanners: Richard White the younger, John Carter, and John Foxall, a relative of an earlier Trustee.